In its century of existence, the Cooperative Extension System has been a valuable resource distributing university-driven, science-based information — mostly about farming and gardening — to the public. But in today's less agricultural America, the Extension network is adapting, expanding its rural focus into cities and suburbs too.

Urban and suburban communities have their own health needs, says Wiley Thompson, a regional director for Oregon State University Extension. "Some live in 'food deserts.' They want to further their education but may not want to move, and many want to intensively garden and manage their compact green spaces," he says.

"I sense the need for Cooperative Extension is stronger than ever," says Thompson, who previously chaired the Department of Geography and Environmental Engineering at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

Cooperative Extension, formalized by the federal Smith-Lever Act of 1914, was designed to translate know-how from technical Land Grant campuses into practical knowledge, and share it with local communities. Most of that outreach was about agricultural production and livestock, gardening, food preservation and safety, nutrition, sewing, early childhood development and 4-H Club activities, says Amy Ouellette, associate director of University of New Hampshire Cooperative Extension.

A century ago, 41 percent of America's workforce was engaged in farming. The comparable figure in 2000 was only 1.9 percent, prompting questions about Extension's continuing relevance.

Over the past few decades, Extension's funding has gone flat or been slashed, its offices closed or consolidated, and its staffing reduced.

"In the early days, about one-third of our funds came from the federal government, one-third from the state and one-third from counties," Ouellette says. "Federal funding has been stagnant. Now it's about 12 percent of our budget."

In New Hampshire, state financial support is funneled through the university system (about 40 percent), while counties contribute about 15 percent, she said. Grants, contracts, fees for service and gifts cover the balance, Ouellette says. Other states use similar funding models.

Despite the cutbacks, most Extension programming is still provided without charge, says Scott Reed, Oregon State's Extension Service director.

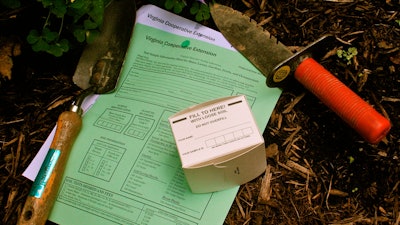

Cooperative Extension remains the one-stop shop for soil test kits, planting information, farm financial health and youth leadership workshops. You can join Extension Agents for field trips to pick out promising calves or lambs for 4-H competition at County Fairs.

"We teach in support of positive youth development, preventive health behaviors, improved water quality, sustainable natural resources, and available high quality and safe food, among other items of public value," Reed says.

Extension is the only deliverer of science-based, unbiased education in rural settings, and can't abandon its rural commitment, he says. But if it's to thrive, it also must go where the people are, he believes, reaching more people through community colleges and virtual learning environments, and through partnerships with educational non-profits and other groups.

Extension's outreach technology already has pivoted toward community settings with hybrid in-person/online courses.

"We have electronic records of those who participate," Reed says. "We know what they're interested in and we go proactive with that."

Education delivery is a crowded field in urban settings with a variety of non-profits and foundations providing services. "In those areas we've become wholesalers of information, expeditors and facilitators, rather than retailing directly to clients," Reed says.

"There's not enough of us to go around."

The new efforts often mean hiring staff with more diverse interests and backgrounds. "We can never forget our roots, but they (staff) must be willing to adapt and innovate both in knowledge and delivery," says Thompson.