NEW YORK (AP) — Would you put down that bag of chips if you saw it had 170 calories? What if the label said it would take 16 minutes of running to burn off those calories?

Health experts for years have pushed for clearer food labeling to empower people to make better choices. In the U.S., a recent regulation requires calorie counts on packages to be bigger. Red, yellow and green labels signal the healthfulness of some foods in the United Kingdom. But with obesity rates persistently high, researchers are looking at whether more drastic approaches could help.

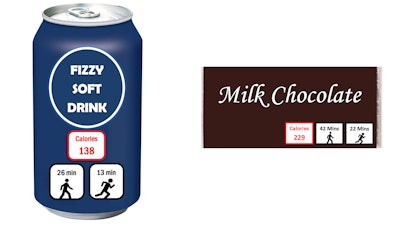

One attention-grabbing idea being explored: Labeling foods with “exercise calories,” or the amount of physical activity needed to burn them off. For example, a chocolate bar might say it has 230 calories, alongside icons indicating that amounts to 42 minutes of walking or 22 minutes of running.

With calorie counts, experts worry the information doesn't mean much if people don’t know how much they should be eating anyway. And with the “traffic light” system, people might not understand why a food is red — is it the fat, the sugar or something else?

It’s no surprise some people don't pay attention to current labels, but exercise calories might be more useful, said Amanda Daley, a professor of behavioral medicine at Loughborough University in the United Kingdom,

“They may still ignore it, but let’s give it a go. Let’s at least give them a chance to be able to easily understand,” she said.

Not everyone finds the idea compelling. Regardless of whether it gets people to eat less, it could reinforce negative attitudes about exercise, said Yoni Freedhoff, an obesity expert at the University of Ottawa.

“The idea that exercise is a punishment for eating does not strike me as a good way to promote exercise or healthy attitudes around food,” he said.

Instead of trying to find a label that can finally persuade people to stop eating unhealthy foods, Freedhoff said it would be better to promote environments where it's easier to make good choices.

For now, it's unknown how exercise-time labeling would affect choices in the real world. Last week, a BMJ journal published an analysis co-authored by Daley reviewing the limited research so far. The review suggested it may lead people to pick lower-calorie items than no labeling at all. But the evidence was less clear when comparing exercise calorie labeling to specific alternatives like calorie counts alone.

The concept may seem too drastic to ever become reality. But Brian Elbel, a New York University public health expert who studies calorie counts on menus, said other measures — such as soda taxes — also once seemed far-fetched.

“Just because it’s not going to happen tomorrow doesn’t mean it’s not an important thing to look at,” Elbel said.