GENTHIN, Germany (AP) — Asparagus grower Henning Hoffheinz is looking at blue skies, a record-early harvest – and a big problem.

The harvest of white asparagus – a ubiquitous and cherished fixture on springtime menus in Germany, frequently slathered in rich Hollandaise sauce – is providing a first test of the fallout from the coronavirus crisis on a farming sector that relies heavily on migrant workers.

The open borders that have characterized the European Union are being closed to prevent the virus from spreading, meaning that tens of thousands of seasonal workers can't reach the farms that rely on them, causing lost revenue for them and the businesses that employ them. In some cases, migrant workers are heading back to their home countries in hopes of living through the lockdown near family.

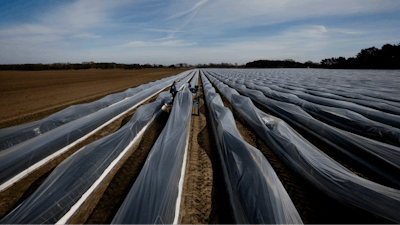

“As things stand, it is not possible to bring harvesters to Germany, which is a disaster,” says Hoffheinz in a field full of asparagus covered with plastic sheeting at Genthin, west of Berlin.

Last year, German farmers employed nearly 300,000 seasonal workers, many from eastern Europe and willing to do heavy manual labor for prosperous Germany’s minimum wage, currently 9.35 euros ($10.25) per hour. Spain has about 15,000 who typically come in from Morocco for the strawberry picking season, which is already under way, and half are expected to stay away this year. Across the EU, some 100,000 come in from outside the bloc to work in seasonal employment.

Hoffheinz managed to bring in 25 Romanians before the borders jammed up – far fewer than the 45 to 50 he will need when the season is in full swing in three weeks. Because of various border closures, “no laborers are coming from the whole eastern bloc, no matter where you look,” he says. He says he'll try to find Germans to do some of the logistical jobs usually done by Romanians – driving the asparagus from the field to a building where it is sorted, and grading the harvest.

“I am sure that we won’t find any Germans for the field work, cutting asparagus, for the minimum wage,” he says.

Germany’s agriculture minister, Julia Kloeckner, this week acknowledged the need to address harvesting 23,000 hectares (56,800 acres) of asparagus fields across Germany, and said more challenges await.

“The asparagus must be harvested,” she said. Beyond that, “we have a planting season, and what isn’t planted can’t be harvested either.”

Many seasonal workers aren’t worried about coming but do worry about getting home without having to go into quarantine, Kloeckner said. She raised the possibility of making bilateral agreements, flying in people who would usually travel overland.

Kloeckner has floated the idea of people who usually work in now-closed restaurants or bars working in the fields. It is time to “consider unconventional or creative solutions,” she said.

On Monday, the German Cabinet loosened rules for seasonal workers, allowing them to stay for longer. And Kloeckner's ministry helped put online a new platform to match up farmers with people who are out of work because of the crisis.

Similar ideas are being floated in Britain, where Brexit concerns had already led to a drop in migrant workers. Seasonal work agency HOP Labour Solutions is, among other things, urging students to help fill in the ranks.

Patrick Wolter, who manages a farmers’ cooperative near Genthin that produces fruit, beef and milk as well as asparagus, usually employs 120 Poles – experienced helpers who have worked there for years – as well as 40 Germans. So far, only six Poles have arrived and “we are trying to get another seven across the border,” he says.

The cooperative has slowed the harvest down a bit, preparing only the fields for which it already has workers and holding off on forcing asparagus elsewhere.

“Right now, we’re living from day to day with the planning, and being surprised every day by new regulations and orders,” he says. “You don’t really dare to make decisions – we ourselves have to wait and see what Germans’ purchasing power will be like.”

He isn’t convinced by the idea of replacing the eastern Europeans with locals.

“Speaking from experience, you can’t handle the work with German people,” he says.

At Hoffheinz's farm, 21-year-old Orasan Claudiu is one of the Romanians who made it to Germany early, and says he's happy to have work for the next three months.

Adrian Bulucz, a Romanian foreman who takes care of bringing in workers like Claudiu, says he will try to bring the full team “if it's possible. If not, we see what happens."

“In Romania now, it is very bad too, because all big companies (are) closed now, don't have work,” he said. People “don't have money and must come here — they wait to come here.”