WASHINGTON (AP) — President Joe Biden is going all-in on calling out "shrinkflation."

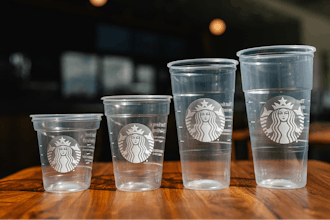

The term applies to a seemingly covert way for companies to raise prices by ever so slightly reducing the size of their products. There's suddenly fewer pretzels in the bag, less toothpaste in the tube and shorter candy bars.

"It's called shrinkflation," Biden said in his State of the Union speech on Thursday night. "You get charged the same amount and you got about, I don't know, 10% fewer Snickers in it."

The president's focus on shrinkflation is part of a broader strategy to reframe how voters think about the economy before the November election. Biden is trying to deflect criticism about high prices and instead pin the blame on big business.

He also is attempting to show everyday people that he's fighting for them as he struggles to convince the public that the economy has strengthened under his leadership.

He talked about the shrinkflation issue in a video released on Super Bowl Sunday and highlighted a social media post by the "Sesame Street" character Cookie Monster that complained about smaller cookies.

The country's low 3.7% unemployment rate and record 16 million applications to start new businesses have largely been overlooked by voters, who are dwelling on higher grocery and housing prices after inflation struck a four-decade high in June 2022 at 9.1%. Even as inflation has drifted down to 3.1% annually, shoppers are still worried about paying a premium at supermarkets.

"Joe Biden recognizes that high grocery prices are an 'Achilles Heel' politically," said Ryan Bourne, an economist at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank. "When consumers are going into the grocery store, they remember that they're paying more than they did in 2019."

But Bourne cautioned that, in the alternative, companies might have simply raised their list prices without shrinkflation, possibly upsetting consumers more and hurting the president's approval on the issue. Just 34% of U.S. adults say they agree with how Biden has handled the economy, according to polling by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research.

"A number of companies did that because they thought that their customers would prefer it to paying higher headline prices," Bourne said. "So I think the president should be very careful what he wishes for when he says he thinks shrinkflation is unfair."

Sen. Katie Britt, R-Alabama, delivered the GOP response to the State of the Union and put the blame for inflation solely on Biden.

"His reckless spending dug our economy into a hole and sent the cost-of-living through the roof — the worst inflation in 40 years," Britt said.

Republicans have claimed that prices jumped because of Biden's $1.9 trillion pandemic relief package, even though the price increases were also global in nature. That's a sign that broken supply chains and higher energy and food prices after Russia's invasion of Ukraine played a role.

In a report published Wednesday, the liberal economic advocacy group Groundwork Collaborative dug into the inflation numbers published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and documented the evidence of shrinkflation, finding it played a meaningful but modest role in higher prices since 2019.

More than 7% of the increase in coffee prices came from reduced packaging. About 10% of the higher prices for snacks and household paper products came from shrinkflation. And for a president who loves ice cream, about 7% of the inflation for that product came from shrinkflation.

Companies might have been masking the higher prices from customers, but they were straightforward with investors on earnings calls, the report said. Some companies such as General Mills have also portrayed the reduced package sizes as a way to manage their own costs and address the challenge of climate change.

The snack company Utz shaved its potato chip bags by half an ounce to 9 ounces, the report said. It trimmed two ounces worth of pretzels out of its pretzel jars, with the CEO heralding to stock analysts its ability to manage what the industry calls "price pack architecture." PepsiCo reduced the size of its Frito Scoops bags, Gatorade bottles and Doritos bags.

"Why we're seeing it now is because shrinkflation is late-stage 'greedflation' — when you've gone as far as you can go in increasing prices and consumers can't take another increase," said Linsday Owens, executive director of the Groundwork Collaborative. "It's much more deceptive than a list price hike."

Sen. Bob Casey, D-Pennsylvania, has introduced a bill that would ban shrinkflation by ordering the Federal Trade Commission to treat it as an unfair or deceptive practice, enabling the government to pursue civil penalties in court against companies that do so.

Biden gave the measure a full endorsement in his speech.

"Pass Bobby Casey's bill and stop this," he said.